To develop functional strength and speed, you need to do more than move weights at the same cadence over and over again. Many athletes focus on the wrong things.

The Nervous System’s Role In Strength

CNS training and ‘quickness’

Bompa (2005) identifies two CNS processes as it relates to sports performance – ‘excitation’ and ‘inhibition’. The speed at which neural signals are sent and received back, results in the eventual levels of excitation or inhibition. For example, to move an athletes limbs as fast as possible when sprinting, the speed of that signal transference throughout the CNS needs to be as fast and efficient as possible. An athlete’s receptors and effectors need to be optimally excited and uninhibited in order to result in the optimum recruitment of fast-twitch muscle fibre.

However, CNS fatigue will slow the that crucial speed of excitation, particularly within a sprinters fast-twitch fibres, which fatigue much more quickly than slow-twitch fibres. Consequently, experts believes training should only be performed as long as ‘quickness’ is possible.

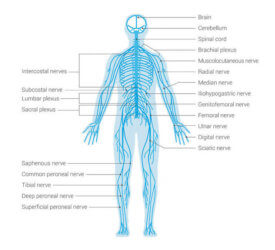

A comprehensive discussion of the nervous and neuromuscular systems can get complex fairly quickly, but there are a few basics that will be helpful in understanding its crucial role.

The nervous system is divided into the central nervous system (CNS) that includes the brain and spinal cord, and the peripheral nervous system (PNS) comprising cranial nerves and spinal nerves. The brain comprises two regions:

- Cerebellum – coordinates muscles to allow precise movements

- Diencephalon – contains two structures:

- Thalamus – acts as a relay station for incoming sensory nerve impulses, sending them on to the relevant areas of the brain for processing

- Hypothalamus – keeps conditions inside your body constant e.g. regulating your body temperature

The nervous system functions as the mechanism that allows your mind and body to work as one cohesive unit. It receives all the input through the sensory nerves and coordinates all this action through our motor nerves. The CNS, consisting of the brain and spinal cord, is connected to our musculature through the peripheral nervous system. That being said, to keep it simple, think of the nervous system as the “battery” that drives your muscles.

Training of the nervous system can be described as “neural adaptation”. When we look at the nervous system as it relates to development of strength, there are two components to focus on and they are speed and power. While physical strength refers to how much force your muscles can give out, power refers to how fast you can exert that strength. It’s the ability to generate large amounts of force over a short period of time as possible. And sprinting speed is the ability to travel any set distance over a short period of time.

We can say that there are four key components for developing our nervous system and optimising the neural adaptation process. Incorporate any one of these into your training, or optimally combine the methods, to greatly enhance your nervous system function, your athletic abilities.

Ways To Optimize Neural Adaptation For Speed & Power

When it comes to optimising your brain and nervous system, recruiting muscle fibers, enhancing nerve firing speed and optimising brain-body coordination, it is important to focus on fast, explosive movements. Here you’ll find some training protocols for developing speed and power, as well as the importance of nutrition and recovery.

1. Challenge Your Body and mind With Overspeed Training

In order to develop speed, you need to train for it and do so as often as possible. A large part of training this is in forcing the adaptation of your nervous system to levels just beyond its current ability. This means getting comfortable with being beyond those limits. A good rule of thumb is if you’re able to think clearly during a speed workout of this kind then you are not training hard enough, or rather not stressing your CNS enough.

Overspeed training is, exactly as it title suggest, its the training method of moving your limbs to turnover at a higher speed that you are used to and comfortable with. Through this method of overspeed training, not only does your brain literally learn how to trigger itself faster and control your muscles more efficiently at higher speeds, but you also develop more powerful and quick muscle fiber contractions called Rate Coding, which comes in handy for hard surges during a race or tough workout. It’s something you can feel but might not be able to put into words. You can sense the brain trying to keep up and adapt to this new level.

There are some things to consider that will increase the effectiveness of speed practice:

- Speed training should be done when you are fresh with no fatigue. Your neuromuscular system is week when it comes to recovery so, speed should only be trained twice a week really. Avoid this type of overspeed work if your system has been exhausted by a hard endurance or strength workout. Consider training either in the morning when you’re fully recharged, or between 2 and 4 PM during your peak reaction time.

- Speed training only really requires brief doses of low volume, high-quality work. This means each session is very short, but very fast, after all its sprinting.

- Overspeed training is primarily about challenging your CNS, not just your muscles. It’s supposed to quickly exhaust your brain while it sends messages to the muscles. Your brain needs a reason to adapt and make this a new normal. Otherwise, you’re not going to develop speed.

Here are some effective training methods for overspeed.

-Downhill overspeed running: I personally use this very often, use a dry, non-bumpy grass area that allows you to sprint for approx 40-50 meters down a slope. Research indicates a downhill gradient of around 5.0% is ideal, . Just run down a gentle hill that isn’t so steep you fall over on your face.

-Overspeed cycling, now this could either be cycling downhil and keeping the gear low so you are “revving” your legs or indoor on a spin bike, the aim to simply get your cadence higher than it would be when you’re running for burst of between 5 to 10 seconds

As with all changes to any training program, be sure to progress slowly to avoid injury and have a sound recovery strategy in pace.

2. Training Strategies For Increasing Power

Power is simply the ability to generate high amounts of force over a short period of time, but isn’t so simple to develop. So as we discussed while your strength refers to how much force yous can exert, your power refers to how fast you can exert that force.

When you train to improve power, your CNS tries and learn to control your muscles in a much more efficient way, creating enhanced muscle utilisation without the bulk. Training for power involves lifting light weights fast, increasing your ability to maximally utilise muscle. The advantage of improving muscle recruitment, without necessarily increasing muscle mass, is that you’ll need to recruit fewer muscle fibres for any given intensity meaning running becomes easier. So power is like putting a V8 engine in your car without increasing the size of the car or the weight of the engine itself. This results in being more efficient and hopefully faster on the track

These are some of the primary ways to improve power!

Plyometrics

Plyometric training is an activity that involves a rapid stretching of a muscle (eccentric phase) immediately then followed by a rapid shortening of that muscle (concentric phase) if we want to be complicated. Hopping, skipping, bounding, jumping and throwing are all examples of basic plyometric movements. Each one of these movements relies upon the stretch shortening cycle concept that when your muscle is rapidly stretched, elastic energy in the muscle’s tendon components is built up and briefly stored in those tendons, and when the muscle then contracts, the stored energy in that tendon is released.

Here are some of the best plyometric movements you can use in your endurance training program:

-Depth jumps: Jump off a raised high platform or box, landing on both feet, and immediately jump back up as high as possible. For this and any other of the leg exercises you should be positively trying to minimise the ground contact time (time on the floor)

-Single-leg hops: One leg, hop up onto a slightly raised surface or box, and back down again readily

-Running Bounds: Running in its fun form, start striding out and then starting running with leap and jump exaggeration

-Clap push-ups: In a variation on the standard push-up, push up explosively, clap your hands, and land. You can do these from your knees if you are not yet strong enough or confident.

-Power skips: where the running bound is a forward projection this one is about getting hight.

-Jump rope: Everyone always forgets about simple skipping with a rope a great workout and plyomentric for the lower legs

Here’s how a sample plyometric routine could look.

- Depth jumps – 10 jumps from 3- to 5-foot box

- Clap push-ups – 10

- Single leg hops – 10

- Med ball throws – 8

- Power skips – 20 yards

- Bounds – 40 yards

- Medicine ball slams – 8

- Hurdle hops – 10 per side

- Jump rope – 20 seconds

You can go through this routine two to three times as a circuit or as little as you need, and unlike most circuits, you’ll want full rest between any sets that use similar muscles (typically between 60 seconds and three minutes). For sets that don’t use similar muscles, such as depth jumps to push-ups, you don’t necessarily need to rest.

Speed-Strength

The only real difference that exists between “strength” and “speed-strength” training is that for speed-strength, you perform the same multi-joint, full body lifts but as you would expect they are performed fast and explosively, most often using lighter weights so that you can indeed move a weight fast. Compared to lifting weights at a slow and controlled speed, which is generally used to maximise strength, explosive training targets movement economy, motor unit recruitment, and even lactate threshold. This is the basis of Olympic weightlifting.

- Dumbbell lunge jumps

- Medicine ball throws

- Medicine ball slams

- Cannonballs

- Chest Throws

- Power Cleans

You should also check out the fantastic and free plyometric and power training library.

To get the most benefit out of your training sessions utilising speed-strength sets, you should generally perform 3-5 sets of just 3-5 repetitions for each exercise that you do, using a weight that is 40-60% of your maximum weight, lifted at maximum speed. Take full recovery between speed-strength sets (2-5 minutes) as much as you need to keep the quality high.

Complex Training

I first came accross this training back in 2000 with a book by Chu,and have never looked back. You may already be aware of the benefits of plyometric exercises and the explosive lifting we have discussed already. But it is slightly less well known that combining the two methods actually increases exercises results in greater muscle fiber recruitment and even faster improvements in power and rate of force development.

“Complex Training” is exactly that: a workout comprised of a strength exercise followed by a plyometric or speed-strength exercise.

Examples of Complex Training include:

- Squats followed by squat jumps

- Lunges followed by lunge jumps

- Front squat followed by drop jumps

- Bench press followed by medicine ball chest throws

- Overhead press followed by overhead medicine ball throws

- Pull-ups followed by medicine ball slams

The proven science behind these matched sets of exercises is that the strength set “primes/sets up” the central nervous system so that more muscle fibers are available for the following subsequent explosive exercise. The difference between the type of strength sets that you perform in a Complex Training vs. a traditional strength set is that your repetitions are lower and heavier in a complex set.

For example, you go heavy on the first set, rest briefly, then progress to the next set, then finally, rest long.

For example:

- Front Squat, heavy x 3, rest 10 seconds, progress to Drop Jump x 6, rest 2-3 minutes

- Overhead Press, heavy x 3, rest 10 seconds, to Med Ball Throws x 6, rest 2-3 minutes

Just like power workouts, Complex Training should be used more than traditional strength training as you get closer to a race or competition.

Each of these strategies, along with tips for developing potent power no matter whether you’re in the gym, backyard, basement, park or hotel room, can be pursued using training tools for increasing power, including power racks, agility ladders, medicine balls, kettlebells, sandbags, adjustable plyometric boxes, weighted vests, training sleds and power cables.

3. Nutritional Support of Nervous System Function

As discussed earlier, the CNS receives input through the sensory nerves and coordinates action through motor nerves. Since the speed that your nerves communicate will directly influence the speed of this process, there’s a great opportunity to introduce food-based supplements into your body that can actually optimise CNS function for speed. Your nerves are wrapped in something called myelin sheaths and a diet optimised for power and speed should be composed of the specific nutrients that support the formation function of these sheaths, as well as the health of the nervous system as a whole.

Two of the most important nutrients for supporting nervous system health are omega-3 fatty acids (especially docosahexaenoic acid, or DHA) and B complex vitamins. Foods such as Flax seeds and walnuts are really excellent sources of omega-3 fatty acids, but the amount of DHA actually absorbed from seeds and nuts is relatively low. Very good sources of more readily available omega-3 fatty acids include oily fish, cloves, grass-fed beef, kale, collard greens, and winter squash, as well as algae-based derivatives like chlorella or spirulina.

From a vitamin B viewpoint, solid plant-based sources are simply the dark leafy greens like kale, bok choy, or Swiss chard. Including those as staples in your diet is very good for the CNS. Organ meats (known as Offal) are another top source of B vitamins.

4. Down-Regulation & Recovery

We’ve talked a lot about the overlooked importance of the nervous system as it relates specifically to speed and power. There is so much-untapped potential in the learning of down-regulation involving the CNS and its inert recovery capacity because as mentioned above, the neuromuscular system is very easily fatigued. Simple things like exercise intensity inclusive of frequency, nutrition, sleep quality, alcohol intake, and even our lifestyle stress all play a part in how we recover. Keep in mind, when your CNS is fatigued from high-intensity efforts or too much stress, it needs as much as 48 hours to fully recover.

So how do you know when you are ready to go and recovered?

Paying attention to your Heart Rate Variability (HRV) provides a valid and comprehensive indicator of your CNS health, and based on your early morning monitored HRV numbers you’ll have a good indication of whether you’re ready for a difficult training session or need to take it easy and recover. You can find some very simple and effective apps in both iOS and Android stores and included within some high tech watches.

Neurotransmitters in CNS Fatigue

The job of a neurotransmitter is to transmit signals across a chemical synapse, such as a neuromuscular junction, from one neuron to another target neuron—the muscle cell. It also carries messages between cells in the brain and spinal cord.

Small sacs called vesicles store neurotransmitters, and each vesicle holds a single type of neurotransmitter. The vesicles travel like tiny little rafts to the end of the neuron, where they dock and wait to be released (presynaptic cleft). When it’s time for the neuron to release neurotransmitters, the vesicles dump their contents into the synapse gap (the space between cells) where they travel to specialised receptor sites.

In exercise and CNS fatigue, the key neurotransmitters are serotonin, dopamine, and acetylcholine (this can be directly supplemented).

Serotonin

Serotonin is linked to our perceptions of effort, lethargy, and CNS fatigue during those prolonged exercise sessions. It’s hypothesised that, during prolonged exercise, brain serotonin levels increase in response to increased blood-borne tryptophan (TRP) delivered to the brain. TRP is a precursor to serotonin. Because of the physiological conditions created during prolonged exercise, TRP circulates loosely bound to albumin, and the free TRP moves across the blood-brain barrier.

Serotonin synthesis increases during prolonged exercise, which is associated with lethargy and loss of motor drive. When brain serotonin activity or TRP availability to the brain increases, fatigue from prolonged exercise occurs more quickly.

Dopamine

Brain dopamine synthesis also appears to be a key factor in CNS fatigue. It seems to be necessary for movement, and increases in brain dopaminergic activity may increase endurance performance. As noted by Davis and Bailey, dopamine may delay fatigue by inhibiting brain serotonin synthesis and by directly activating motor pathways. Dopamine increases neural drive as well as motivation.

With ideal dopamine levels, athletes may want “it” more. They may want to train more and be hungry to compete. Dopamine also seems to increase vasodilation and the sweat response. The general theory is: more body heat, better nerve impulse transmission. Consequently, CNS drive is enhanced and fast twitch fibers are reached due to their superficial nature.

Summary

Use of overspeed training, smart power development, nutritional support, and recovery all combine to support neural adaptation in strength development. Awareness and optimisation using the above methods to enhance the nervous system will lead to massive gains in power and speed.